2025 ACM Awards

We’re beyond thrilled to celebrate our incredible MAX artist partners who’ve secured nominations for the 2025 Academy of Country Music Awards—our...

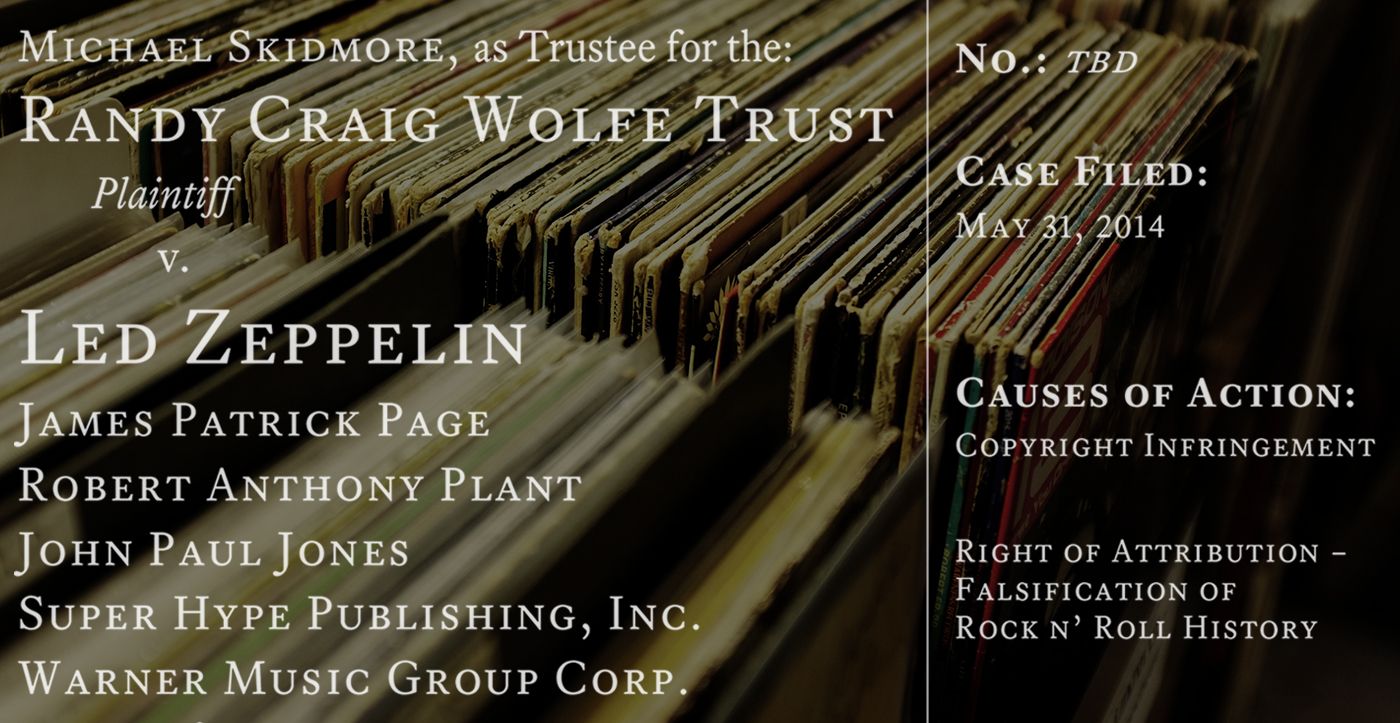

This is the third article in an ongoing educational series on the MAX Blog. Read the second article, “Led Zeppelin Wasn’t Guilty Of Copyright Infringement, But You Still Might Be” here.

Check out the SXSW Panel organized by the author of this article here.

George Howard, MAX’s Head of Music and Cofounder, recently analyzed a copyright infringement suit involving the members of Led Zeppelin and the band Spirit. In the article, he concluded:

With an increased proliferation of music, and a similarly increased ability for artists to create and distribute music, the opportunities for both exploitation and infringement of music are more pronounced than ever.

About a week later, the rightsholders associated with Marvin Gaye’s works sued Ed Sheeran over alleged similarities between Sheeran’s Grammy-winning “Thinking Out Loud” and the song “Let’s Get It On,” which was performed and co-written by Marvin Gaye.

In this article, George unpacks this most recent case and provides recommendations for artists to best navigate the increasingly litigious realm of the music industry.

When an artist creates an original work of authorship, he or she is immediately granted a set of exclusive rights.

These rights, further enumerated in the Led Zeppelin article, essentially disallow the sale, distribution, streaming, broadcast, etc. of an author’s work without license or approval.

It’s fairly straightforward when one party willfully and blatantly copies the work of another. However, issues arise out of ambiguity related to:

Interestingly, this is neither the first time Ed Sheeran has been sued for infringement, nor is it the first time that rightsholders associated with Marvin Gaye’s works have sued.

In June, Martin Harrington and Thomas Leonard sued Sheeran over similarities between their song, “Amazing” and Sheeran’s work, “Photograph.”

Similarly, the Estate of Marvin Gaye was awarded a multi-million dollar judgment (later reduced) against Robin Thicke, Pharell Williams and a host of other writers over similarities between Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” and Gaye’s “Got To Give It Up.”

Now, the estate of Ed Townsend, one of the writers of “Let’s Get It On,” has sued Sheeran over alleged infringement for his song, “Thinking Out Loud.” As The Washington Post reports:

The Defendants [Sheeran, et al.] copied the ‘heart’ of ‘Let’s’ and repeated it continuously throughout ‘Thinking,’ ” the lawsuit said. “The melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic compositions of ‘Thinking’ are substantially and/or strikingly similar to the drum composition of ‘Let’s.’

Take a listen for yourself:

It’s obviously possible to accidentally/unconsciously copy the work of another. There are only twelve notes, so... what is an artist meant to do?

Even George Harrison, certainly someone capable of creating original works, lost a 1983 infringement suit for “unconscious copying” via the similarities between his song "My Sweet Lord" and The Chiffons' "He's So Fine."

This idea of unconscious copying emerged in 1924 via an opinion by Learned Hand (the judge who absolutely wins the best-name contest):

Everything registers somewhere in our memories, and no one can tell what may evoke it . . . . Once it appears that another has in fact used the copyright as the source of this production, he has invaded the author's rights. It is no excuse that in so doing his memory has played him a trick.

Essentially, Hand espoused the “unconscious copying” of another’s work is an invalid defense.

For an infringement claim to succeed, the alleged infringer must have had “access” to the original work. However, this was more of an issue in the pre-Internet era than it is in current times - when most everyone has access to most everything, via Spotify, YouTube, et al.

The issue currently troubling artists relates to an increasingly vague set of standards of what constitutes infringement. For example, the judgment against Thicke, et al. appears to be based upon similarities of “mood” or “vibe” rather than on more traditional criteria; such as. musical structure.

In a similarly vague manner, the “Thinking Out Loud” suit uses “rhythmic compositions” as one of the relevant elements for its infringement claim. This is especially troubling because rhythms have historically have been deemed lacking sufficient originality to be copyrightable.

More than anything, though, the increasing frequency of the copyright suits is worrisome. Raymond Kurzweil asserted about the perceived rise in global violence’s that “the world isn’t getting worse - our information is getting better.” I agree with this, and, it strikes me that decisions like that rendered in the “Blurred Lines” case have encouraged rightsholders to issue more suits - however tenuous in nature – in the hope of receiving a similar judgment.

It is perhaps not coincidental that as rightsholders make less money from their music through traditional methods, they increasingly look for alternative forms of revenue (such as lawsuits) to reclaim some of the gap.

Artists SHOULD NOT stop creating works.

Copyright laws, and laws in general, are predicated on the idea of balancing the rights of the individual with the good of society. In no circumstance is it a positive outcome for artists to decide the legal risks of creating art are so high that it’s better to just stop making music.

Instead, artists should make an effort to understand what their rights are, and therefore understand how/if they may be infringing on the works of others. Once an artist understands that only he has the exclusive right to create derivatives of his work, he is less likely to sample the works of another without proper permissions.

If and when artists become aware of what may be a substantial similarity between their work and the work of another, the potentially infringing artist should attempt to address the situation.

For instance, Sam Smith and his management team reacted swiftly and appropriately to the similarities between Smith’s song “Stay With Me” and Tom Petty’s “Won’t Back Down,” which Petty addressed by saying:

About the Sam Smith thing. Let me say I have never had any hard feelings toward Sam. All my years of songwriting have shown me these things can happen. Most times you catch it before it gets out the studio door but in this case it got by. Sam’s people were very understanding of our predicament and we easily came to an agreement. The word lawsuit was never even said and was never my intention. And no more was to be said about it. How it got out to the press is beyond Sam or myself. Sam did the right thing and I have thought no more about this. A musical accident no more no less. In these times we live in this is hardly news. I wish Sam all the best for his ongoing career. Peace and love to all.

While an established artist like Smith can more easily reach an accord with Tom Petty than an emerging artist, the gesture of preemptively recognizing something that wasn’t caught “before it [got] out the studio door” shows good faith. While this gesture doesn’t address the issue entirely, it can impact a legal outcome.

The bottom line is, if you as an artist feel or know that your work may be substantially similar to that of another, you should take efforts to either make it less so, or to secure the appropriate licenses from the rightsholders. While the line between originality and infringement does appear increasingly...ahem...blurred, the burden still rests on the songwriter to understand their rights and address issues that arise. Wouldn’t you want and expect the same from others who might be copying your work?

Vote for George Howard's SXSW Panel here.

We’re beyond thrilled to celebrate our incredible MAX artist partners who’ve secured nominations for the 2025 Academy of Country Music Awards—our...

We’re fired up to celebrate our incredible artist partners who are nominated for the 2025 Blues Music Awards! 🎶🏆Blues music may be timeless, but...

It’s a common question: what drives the cost of an artist partnership up (or down)? I mean, an artist’s fee can range from four to seven figures…and...

What You Need to Know to Protect Yourself This is the second article in an ongoing educational series on the MAX Blog. Read the first article, “PROs:...

Here in Dallas, it’s sunny outside but sometimes it still feels like we’re living in the shadows. Let me explain.

Amidst all the talk of royalties and copyright infringement, it’s easy to forget that music is about more than business. At Music Audience Exchange...