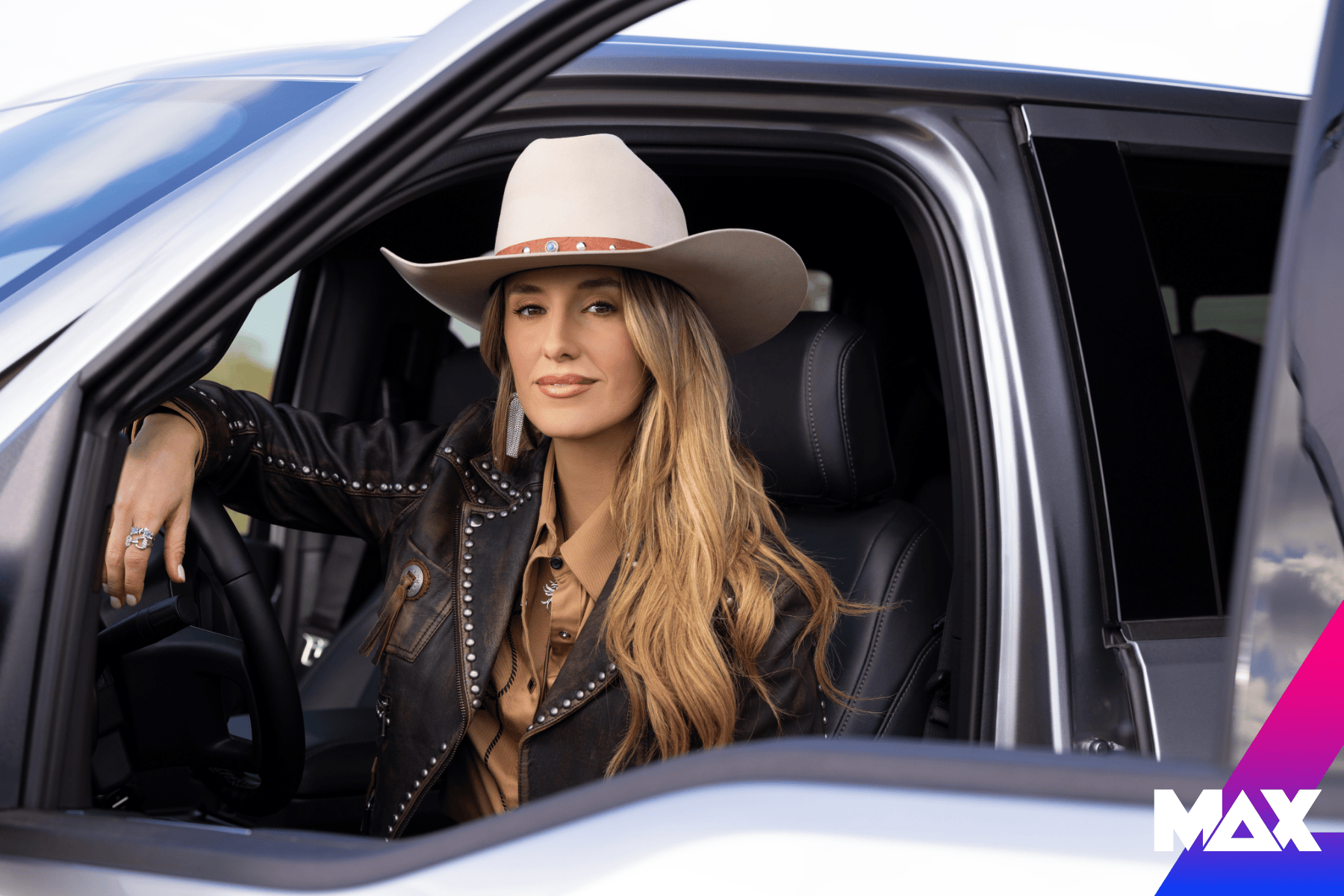

Lainey Wilson × Ford Truck Month 2026

Lainey Wilson is back for another Ford Truck Month celebration! And she's bringing a brand new song to this partnership, along with a git-up-and-go...

George Howard, Co-Founder and Head of Music at MAX, is an associate professor of music business and management at Berklee College of Music, a top music business school in the US, and Brown University. The former President of Rykodisc and one of the original founders of TuneCore, Howard holds an MBA and a JD.

Here, Howard continues on his introduction to publishing, mechanical licenses, and public performance with an introduction to syncs.

As music fans have shifted from purchasing albums to downloading songs to primarily listening through streaming services, sync deals have grown more and more appealing to artists and managers.

The word “sync” is short for “synchronizing music with a visual image.” This generally refers to when a song is used in an advertisement, television show, or movie.

Today, syncs have, in some regards, become the new radio. In other words, many artists and managers now believe that synchronizing music to advertisements, television shows, and movies will most effectively allow them to reach wide audiences.

Many of the ways artists and managers have historically reached fans at scale - such as press, radio, and touring - have become less reliable. Even social has become an increasingly challenging medium to gain traction.

Of course, in addition to the exposure a sync deal might bring, there is sometimes an additional revenue component (some of which is described in a recent article about PROs) that further appeals to managers who, increasingly, find revenue for their artists elusive.

Given the mass exposure and revenue potential, it’s understandable why so many artists are more interested than ever in learning about syncs. Unfortunately, as with so much in the music industry, most artists do not understand how the process works. This walkthrough will shed some light on the subject.

Before approaching the mechanics of a sync deal, it’s first important to understand what it takes to get music synchronized. Like all other aspects of the music industry, music does not just get noticed. The music supervisors in the entertainment industry and the decision-making executives at ad agencies are unlikely to simply stumble upon great songs. Almost every artist starts by gaining traction in a local market.

As an artist, manager, songwriter, or anyone interested in getting mass exposure for music, success depends on this traction. Artists must build a hysteria around their music, with more progress occurring as fans get increasingly energized.

Once fans start to respond favorably to music at live shows, forward motion begins. A great live show leads to connections and opportunities like:

Opportunities lead to more opportunities, and traction leads to interest from people who can guide more traction, ranging from lawyers to well-connected managers to booking agents, and more. As forward motion progresses, artists may get a key gig in Los Angeles. or a radio station like KCRW in Santa Monica may offer airtime. And because of this, one of the many people in the entertainment industry who listens to KCRW—music supervisors, film directors, etc.—might hear an artist, check out a live show, and decide to include one of their songs in an upcoming film. This traction, this demonstrated motion, is critical.

As referenced in MAX’s recent introduction to mechanical licenses, a music supervisor or ad agency exec looking to synchronize a song needs access to two separate copyrights:

The parties holding the © and the ℗ each have the exclusive rights to control reproduction and distribution. This especially important because anyone licensing a song must have permission to reproduce and distribute the copyrighted work.

The party licensing the song must strike a deal with the copyright holder(s) to avoid infringement on their exclusive rights. Considering that every song has two copyrights, two deals must be struck:

Long story short, a music supervisor looking to sync a song will typically work with both the songwriter (© holder) and the party that controls the master (℗ holder) to attain proper rights to sync a song.

Songwriters and master recording holders generally receive consistent terms, something known as an MFN (Most Favored Nations) deal. This is critical to understand. If, for example, the © holder successfully negotiates better terms, the MFN clause allows the improved terms to extend to the ℗ holder as well.

Similarly, if the ℗ holder accepts a deal but the © holder denies the deal, the deal is off for everybody.

However, if the © holder agrees to a sync deal but the ℗ holder declines, the music supervisor can bypass the ℗ holder by re-recording the song. This is why many songs are considered “re-mastered.”

If the song (composition) has multiple copyright owners (© holders), all must agree or the license does not happen. For example, if John Lennon’s publisher (© holder) agrees to a sync deal but Paul McCartney’s publisher does not, nothing will happen.

For a music supervisor or artist looking to strike a sync deal, the path of least resistance occurs when the songwriter owns his or her master recording. This way, one single person can approve both sides of a deal (i.e. the © and the ℗) AND get paid double.

It’s worth reiterating, however, that as the music industry has evolved, more and more artists are eager to sync their songs to movies, television shows, and advertisements. With more options than ever available to music supervisors, song usage fees have drastically decreased.

Successful, popular artists can obviously command higher fees than less-established acts, but there’s less consistency than in the past. Of course, the type of usage will play a factor in the fee. A song playing during the title sequence of a major studio film will command a higher fee than a song that plays for 5-seconds in the background of, for example, an Amazon Prime original series.

The deals between the producer of the TV show/movie/ad and the master and composition holder(s) will also address specifically how the song can and cannot be used. When rightsholders agree to have their music used in a TV show, for instance, the deal will outline terms related to how streams, rentals, and various other uses affect the song’s rightsholders.

Just like the rights of replication and distribution, © holders have another exclusive right: public performance. This essentially means that the songwriter (or, more likely, the Performance Rights Organization representing the songwriter), is due a payment every time his or her song gets broadcasted.

In regards to sync deals, this means that the © holder generates additional revenue whenever the song gets played in a television show, movie, or advertisement. In the US, this right does not transfer to the ℗ holder, regardless of how the MFN clause affects initial negotiations.

Synchronizations are big business and in high-demand these days from artists. Having music used in a movie, television series, or advertisement can be a huge opportunity - both in terms of revenue and awareness-building. However, before jumping in, it’s worth taking the time to understand potentially complex rights issues and possible pitfalls.

Lainey Wilson is back for another Ford Truck Month celebration! And she's bringing a brand new song to this partnership, along with a git-up-and-go...

Our latest Ford Truck Month campaign is here! Latin music star Carolina Ross joins the Música Ford family to drive affinity and consideration for the...

Hard to say... super easy to eat. The Ton3s got to try the McDonald's Crispy Chicken Biscuit with Hot Honey—and they're lovin' it!

George Howard, Co-Founder and Head of Music at MAX, is an associate professor of music business and management at Berklee College of Music, a top...

Below is an excerpt of a live interview between Cheddar Media and MAX Co-Founder George Howard. This has been briefly edited and condensed to...

Amidst all the talk of royalties and copyright infringement, it’s easy to forget that music is about more than business. At Music Audience Exchange...