2026 GRAMMY Awards

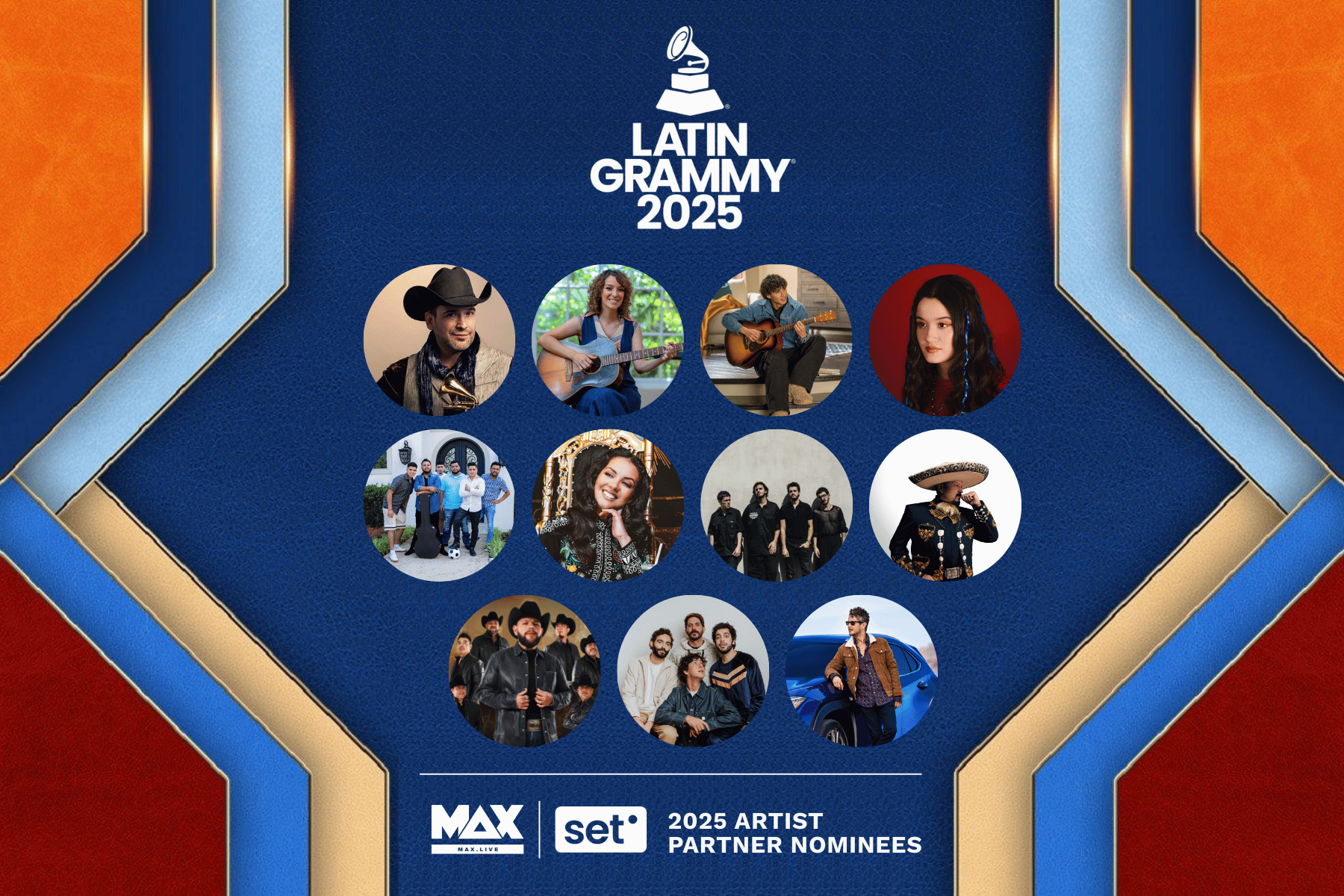

Y'all, 38 artists and 70 GRAMMY nominations is BONKERS!! Our MAX/SET artist partners absolutely crushed it this year.

4 min read

George Howard : October 6, 2017

George Howard, Co-Founder and Head of Music at MAX, is an associate professor of music business and management at Berklee College of Music, a top music business school in the US, and Brown University. The former President of Rykodisc and one of the original founders of TuneCore, Howard holds an MBA and a JD.

Here, Howard continues on his introduction to mechanical licensing.

Songwriters have historically generated the most revenue in the music business, due in large part to mechanical licenses. It’s something that every songwriter must understand.

To recap, a mechanical license is an agreement between a party (typically a label) who desires to reproduce and distribute a songwriter’s song.

Mechanicals have been around since the dawn of the recorded music industry, originally existing to compensate for “mechanically” reproduced works on piano rolls and music boxes.

As the music industry has evolved the revenue generated by these songwriters grew in direct proportion. This manifested across the emergence of labels and new music formats like vinyl, cassettes, CDs, and downloads.

Through all of this, songwriters who wrote songs that were later recorded by successful performers received mechanical royalty payments from the labels who released the recordings on behalf of the performers. Consider the situations below:

In all of these instances, the songwriters made money via mechanical licenses from the labels representing the performers.

Singer-songwriters signed to a label often receive vastly more money from mechanical royalties than from royalties related to record sales. With zero exceptions, those in a band who write the songs make more money than those who do not because of mechanical royalties (and other royalties -- such as synchronization and public performance -- which are also paid to the writers, and only the writers). Bands break up over this discrepancy.

As music consumption has firmly moved from vinyl to cassettes to the streaming era, mechanical royalties continue to be relevant.

However, Spotify, the most popular music streaming service, is currently advancing a theory against paying mechanical licenses. Spotify is arguing that they do not owe a mechanical license to songwriters because the copyright code stipulates that a mechanical license is required for reproduction and distribution. Essentially, Spotify argues there is no reproduction in a stream, and thus no mechanical royalty due. To date, songwriters have been owed a mechanical from streams.

As Spotify advances its argument against mechanical licenses, songwriters and their representatives -- such as their individual publishers and organizations, like the NMPA -- will continue to counter this statement.

With governmental statutes dictating mechanical rates, rather than the negotiated rates labels receive for sound recordings, songwriters already lack leverage with mechanical licenses. Should Spotify get its way, songwriters will have an extremely difficult road forward.

As mentioned above, governmental statutes set the price for mechanical rates. This concept, known as a statutory rate, leads to an important point that all artists must understand.

The copyright code includes a provision allowing any commercially-released song to be “covered” (that is, re-recorded) by any other artist, as long as the artist who covering the song abides by the statute’s rules.

For example, if an artist decides to cover Bob Dylan’s song, “Masters of War,” Bob Dylan cannot prevent it. However, that artist must abide by the rules set forth in the statute, such as:

Failure to comply to any of these rules could put an artist at risk for an infringement claim brought by the writer or his/her publisher (Bob Dylan, in this example).

When artists decide to cover and release works they did not write, it’s very important that they either:

The “Controlled Composition Clause” refers to a part of the agreement that a performer enters into with a label.

This clause defines a “Controlled Composition” as any song that the performer who is signed to the label wrote, co-wrote, or has any financial interest in. Essentially, the performer “controls” the work. It is not a cover.

While the copyright code sets a specific (statutory) rate to pay a songwriter when covering their work, it does not specifically stipulate that the rightsholder of the composition must get the full amount.

In other words, based on the deals they sign, songwriters can knowingly or unknowingly accept lower rates than what is statutorily set.

Of course, if you're Bob Dylan, you’re going to deny a request for a lower rate from someone who covers your song.

However, if you are an emerging singer-songwriter and the label signing you asks for a lower rate, you are more likely to accept, If you do deny this “request,” the label could simply decide against signing you.

Labels have wielded this controlled composition clause for decades to reduce the amount they pay their artists. In fact, artists who sign to a label and write their own songs will typically only receive 75% of what would be due based upon a statutory rate.

The label’s response is that they are the “engines” for these mechanical royalties -- via marketing and promotion -- and therefore should not have to foot the entire mechanical bill.

If you’re an artist, can you negotiate out of such a Controlled Composition Clause? If you are very successful or very in-demand, maybe. But, if you don’t understand how mechanicals work, you will not even know to try.

And that is the main point of this entire piece: publishing, generally, and mechanicals, specifically are both tricky topics. It can take a long time (and, often, a law degree) to fully grasp the nuances.

However, for any songwriter, there is simply no other business detail more important to understand. Put simply, a mechanical is due to you as a songwriter any time your song is reproduced and distributed, whether you perform it or someone else covers it. These songs are your precious assets and must be protected.

Y'all, 38 artists and 70 GRAMMY nominations is BONKERS!! Our MAX/SET artist partners absolutely crushed it this year.

11.17.2025 UPDATE: 4 artist partners took home Latin GRAMMY Awards! 🏆🍾 The countdown has begun for the 2025 Latin GRAMMYs! On November 13, 2025,...

The 2025 CMA Awards, airing on November 19, 2025, will celebrate the best in country music, and we're thrilled to announce that 14 of our incredible...

George Howard, Co-Founder and Head of Music at MAX, is an associate professor of music business and management at Berklee College of Music, a top...

I’m digging the article from the INgrooves newsletter that was re-blogged by the always great Hypebot (and linked to below). There are some good...

George Howard, Co-Founder and Head of Music at MAX, is an associate professor of music business and management at Berklee College of Music, a top...